KARGIL: Recently, Kargil was in the news as an election was round the corner. And, as soon as the elected candidates took oath, it vanished from the media – again.

Even during the election, no due coverage was given to the issues of the people of this isolated region – their challenges, demands and achievements were all missing from the news. How despite the extreme weather conditions, tough geography and few resources, the Kargili community is surviving efficaciously? And, when the struggle is seen through the lens of gender, the achievements become even more interesting.

Draped in colourful hijabs, seemingly delicate yet confident enough to speak their mind, are the members of Kargil Town Women Welfare Committee – an all women non-profit organisation working towards empowerment, socially as well as financially. An effort of this magnitude, often taken for granted in a metropolitan as well, requires a different kind of courage altogether in a region as remote and conservative as Kargil.

This cold desert was virtually unknown to the rest of India until the international neighbours forced it sharply into focus during the famed Kargil War in 1999. Struggling to reconcile with the losses inflicted during the war, Kargil became a crucial mark on the Indian map. With its newly-established link with the rest of the country, Kargil began to abandon its traditional conservative notions and witnessed men and women welcoming change with open arms.

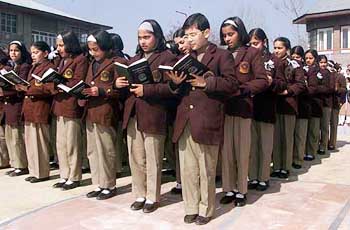

A society where educating girls was an alien concept until the late 80s had now women venturing into every possible arena. Financial empowerment of women gained major significance amongst educated and uneducated women alike.

Fiza saw women using mud instead of soap to do the dishes. Inspiring stories from daily TV soaps prompted her to change their lives.

Founded in 2009, the Kargil Town Women Welfare Committee is the brainchild of 24-year-old Chanchik town-based Parveen Akhtar, hailing from a well educated family in rural Pashkum.

Over the years, the members of this committee have helped sanitise the town by opening roadside latrines, improving drainage systems and guarding and fencing the riverbank; and even helping install a transformer in the town. With its office centred in one of the member’s house, this committee also makes a range of jute bags and other products which is sent to the Mata Vaishno Devi Trust and other States, generating some income for its members.

Working relentlessly for the same purpose is Fiza Bano who runs the Tribal Women Welfare Association which includes carpet making and wool cleansing, in addition to tailoring and knitting. Started with just five members and a small quantity of wool worth a mere ‘500, her NGO is now a proud income source for nearly 100 women members.

“I have seen women using mud instead of soap to do the dishes”, laments Fiza. Conditions of such financially challenged women and inspiring stories from daily TV soaps prompted Fiza to undertake this noble task.

These women with their recipes for positive changes present a cheerful picture of Kargil. However, given the unpromising attitude of those in power, this picture seems to get foggier by the day.

In a world patterned by assumptions and values of patriarchal culture, it’s an exceptionally challenging task for a woman to run an NGO, bearing the weight of hope of many. Despite the Government having provided myriad schemes, grants-in-aid for NGOs and particularly for women, these schemes have remained locked up in the policy sheets.

Parveen Akhter, who keeps herself updated with these schemes and policies online, claims that the departments responsible for executing these schemes refuse to even disclose them to her committee members. An application sent by her committee members to fetch them some wage earning tasks is disregarded in favour of a male committee member, clearly subscribing to the cliched gender dichotomies. Before undertaking the sanitation task in town, the Municipal Corporation had been approached for “precisely ten times”, recalls Parveen.

These women with their recipes for positive changes present a cheerful picture of Kargil. However, given the unpromising attitude of those in power, this picture seems to get foggier by the day.

Crores of funds that the Council receives, tribal funds and border funds are all sent out to male societies leaving these women with scarce resources at their disposal. While the handicraft sector claims to have granted Share Capital Assistance and schemes under Formation of Handicraft Industrial Corporation, these women have a different story to share. They believe that the Handicraft and Handloom sectors’ schemes are confined exclusively to their respective department workers.

While these offices are flooded with funds from both the State and the Centre, Fiza Bano still awaits her project’s approved, pending with the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs office for three years now. Their call for an All India Handicraft Office in the town and a Committee Hall for women remains unattended to; while Leh and Kashmir get feted with the same. To top it all is the societal criticism these women have to encounter owing to the conventional, orthodox mindset.

Blitzed with constant criticism from the orthodox minds of society and the disappointing ‘gender insensitive’ outlook of the higher authorities, the efforts made by these women-led NGOs appear to garner nothing but an endless treadmill. And it won’t take long to render these women voiceless again in the deafening din of the patriarchal crescendo.