Sheikh Saleem

I remember once during my childhood I insisted my father to take me to the parade ground on August 15. I was eight years old; I wanted to see the flag being hoisted. I had seen the celebrations of Independence day on television – smiling people, distribution of sweets and the excited children. That day, I too was excited. So much so that I wore chappals of two different colours – something that I realized only at the end of the ceremony.

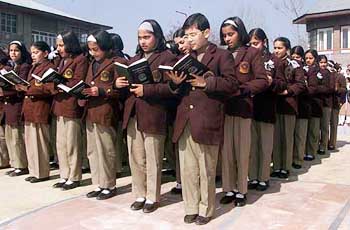

For me, Independence Day was the day when army and a local elder would distribute sweets and notebooks among the kids who were incidentally the only audience at the parade.

For five years, I was a regular at the ceremony before I stopped. It has been twelve years since. Today, it is India’s 66th Independence day. Today, as all the means of communication were barred in the valley, it took me back to those days when valley was not allowed to launch mobiles services, when people were kept at bay from internet just because India didn’t want the outside world to know about our pain. And like childhood, as there was no internet to surf or working cellphones to call my friends, I reverted to an old diary – my childhood diary.

On one of its pages, I had written an Urdu poem. It was dated August 15, 2000. Let me quote a few lines:

Kya ab bhi Captain Raj Logu ko Dhamkata Rehta hai, (Does Captain Raj still threaten the people?)

Kya ab bhi Nawjanu ko Peeta jaata hai. (Does he still beat up youngsters?)

Kya ab bhi Naray Lagtay hain, Jalsu mai, Azadi kay, (Do they still chant slogans of freedom at rallies?)

Kya Ab bhi makanu ko zamin boos kiya jata hai? (Are houses still razed to ground?)

I don’t remember what exactly prompted me to write these lines. But yes, I remember Captain Raj. He was an army captain in my town, all were scared of him. Probably, it was he in the first place that I wrote.

It was August 14. I was only 13. I was standing near my shop in the town waiting for my father’s return. Captain Raj was in the market not to hunt for any militants but to haunt the shopkeepers, pedestrians and the drivers. He was looking for a shop, a bus or car that is without the Indian tri-colour. Any one who didn’t have the Indian flag hoisted in his shop was beaten.

My neighbouring shopkeepers advised me to bring a flag and hoist it in the shop. I didn’t listen. I had a different image of the army – the images of distributing sweets among the children. How could they beat me? I had also read in my civics book that no one can could force others to hoist the flag.

But my perception of the army changed in the next five minutes. Captain Raj pulled me out of the shop, slapped me thrice on the face and then hit me on the back with his jackboots.

And for them it was not enough. His loyal guards demanded an identity Card from me. I was 13 and a possible militant because I could not prove my identity to the outsiders in my own land. The punishment was 20 ups and downs.

I returned home. In the evening, I wanted to visit my uncle’s home. I took my cycle and left. But even then the flag was missing. I had to pass through an army camp and was told that they don’t allow any vehicle that doesn’t have a tri-colour on it. I was relieved. I had only a bicycle, not a vehicle I thought. But as I reached near the army camp, a uniformed man came out of the bunker to check the flag on my “vehicle”. As he didn’t find any, I was forced to hold the cycle on my shoulders and walk a distance of 200 meters as a punishment.

That was the incident that changed my perception. Next day, I relieved papa of the “duty” of taking me to the parade ground. Sitting at home, instead, I wrote the lines in my diary. I dont miss anything, only they lost one among the audience that day!

(The views are author’s own. The organisation does not necessarily subscribe to the views)