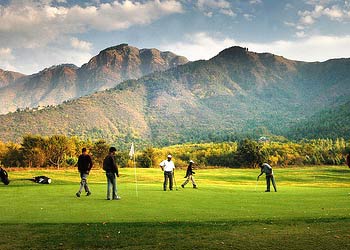

NEELAM VALLEY: Ashraf Jan often visits this particular spot in northern Kashmir where the Neelum river cuts a narrow passage through a mountain village, leaving it divided between two steep hills.

She stares at the wooden houses across the river, and points to one of them.

“A very old couple live there – they are so old they don’t come out of their room any more. They are my father and mother,” she says, fighting back her tears.

Even though Ashraf Jan, who is 40, lives just minutes away from the house, she hasn’t been there in 22 years.

That’s because the divide here runs deeper than the river, and she’s standing on the wrong side of it.

In 1948, India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir. The war ended with them dividing the region along a de facto border, the Line of Control (LoC), which is still disputed – and often violent.

In Keran village, this line passes along the river, and since a 2003 ceasefire, it has become a convenient point for divided families to assemble and wave greetings from opposite banks.

Siddique Butt, 65, is here to wave a hello to his daughter.

“She was sitting up there a while ago,” he says, pointing to a clutch of houses higher up on the same hill. She’s married with four children. She recognises me when I walk on the riverbank.”

‘Alienated’

Ashraf Jan and Siddique Butt are among roughly 30,000 people who fled their villages on the Indian side of the LoC in or about 1990, when a violent separatist insurgency broke out in Indian-administered Kashmir, the country’s only Muslim majority state.

They crossed to the Pakistani side where they were housed in temporary camps, hoping to return home soon when the conflict was resolved. But that didn’t happen.

During a decade following the uprising, another 30,000 youths from the Indian side are believed to have crossed over to receive training and arms to fight Indian forces in Kashmir.

Most of them went back to carry out attacks on Indian targets. Many were killed or captured, while some managed to slip back into normal lives in homes they had once abandoned.

Today some 3,000 to 4,000 of them remain in Pakistani-administered Kashmir – many of them are now middle-aged and have families.

These displaced Kashmiris – who number more than 36,000 in all, according to officials in Pakistani-administered Kashmir – find themselves increasingly alienated as Pakistan mends fences with India, and the insurgency winds down to a mere shadow of what it once was.

The divide along the LoC remains as deep as ever, however.

‘Fading militancy’

Defence analyst Hasan Askari Rizvi says these people are caught in a “time warp”.

“The insurgency kept Kashmir on the boil for well over a decade, but failed to shake Indian rule, prompting many quarters to question its justification,” he says.

“Also, the insurgency passed into the hands of religious extremists, which made it unpopular internationally, especially after the 9/11 attacks in the US.”

Pakistan, then under pressure to severe links with militant outfits, took a series of steps to wind down the Kashmir insurgency.

In 2003, it agreed to the ceasefire with India across the LoC. In 2006, it stopped all funding for militant operations in Indian-administered Kashmir, ignoring protests by some of the more influential groups such as Hizbul Mujahideen (HM).

Earlier this year, it cut by half the administrative funds it issues to insurgent groups that still maintain offices in Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

Alongside this financial squeeze, Pakistan offered a cash rehabilitation package to former fighters to get married and set up businesses.

These steps sparked a chain of events that further diluted militancy.

India’s military took advantage of the ceasefire to fence the entire LoC, which it now monitors electronically making infiltration by militants more difficult.

On the Pakistani side, communities along the LoC who had virtually lived in bunkers for 16 years rose up in protest against any hint of militant activity that might endanger the ceasefire.

These protests forced local authorities to relocate militants to areas away from the border region.

On the Indian side support for militancy has also dwindled.

People there had backed the uprising of 1988-90, but things began to turn sour for them when infighting broke out between pro-independence nationalists – who had kick-started the insurgency – and Kashmiri Islamists who wanted Indian-administered Kashmir to accede to Pakistan.

Although they prevailed initially, the Islamists too became increasingly frustrated when by the mid-1990s many hardline Pakistani groups – such as Harkatul Mujahideen, Al-Badr, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad – joined the fray.

These groups brought with them greater resources to eclipse local Kashmiri groups, and professed foreign religious ideologies that were less tolerant of local sensibilities.

According to conservative estimates, more than 50,000 people died in about 20 years of conflict, most of them civilians.

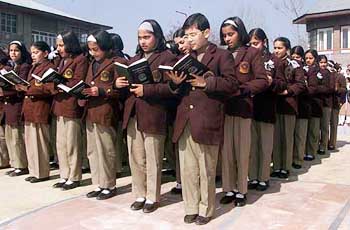

The prolonged and heavy militarisation of the region played wrecked people’s lives and ruined the economy, as well as depriving a generation of proper education and normal upbringings.

By the mid-2000s, the downside of the conflict was becoming obvious.

Irshad Mehmood, an expert on Kashmir affairs, describes the lessons the Kashmiris have learnt from this “bitter experience”.

“Today’s Kashmiri youth know that the blood-letting of all those years didn’t bring them an inch closer to independence. They also know that armed conflict has damaged some of the best values of their society.”

The new mood in Indian-administered Kashmir is to switch to a movement of civil liberties and human rights, which has not only attracted international attention, but also drawn sympathy from the Indian media itself, he says.

This change of thinking on both sides of the divide has put most Kashmiri militant groups out of action, and Pakistani groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba have seen their foothold in Kashmir steadily weaken.

“These [Pakistani] groups cannot keep the insurgency going, because they cannot operate without local support,” says Dr Rizvi.

‘No future’

But while the scene in Kashmir is changing for the better, the circumstances of the people who were displaced from their homes 22 years ago have gone from bad to worse.

Once literally coaxed by Pakistani border officials to cross over, they now form part of an unwanted population that is denied both citizens’ rights in Pakistan and access to their former homes.

For militants, the journey has been from freedom fighter to refugee living in one of the miserable, crowded tent villages in the slums of Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

“My children have no future here,” says one dejected former fighter, requesting anonymity.

“They can’t have a Pakistani national ID, which means they can’t have a passport, a decent job, or any other rights. We are living in a trauma.”

As the dream of liberation recedes, the urge to return home grows stronger. It is further fuelled by an Indian offer of amnesty.

But neither the Indians nor the Pakistanis want these people to return to their homes all at once.

For India this could create security risks and administrative bottlenecks. And Pakistan fears negative publicity – most refugees are disappointed with life there and might speak up once they are out of reach of Pakistan’s “unforgiving” intelligence services.

To prevent this, the two countries do not allow public movement across the heavily militarised LoC.

They have kept refugees off a bus service that began in 2005 and is the only transport link between the divided parts of Kashmir. Officials on both sides strictly screen passengers before issuing travel permits.

‘Alternative’

But since January 2011, the two countries seem to have collaborated in opening an alternative route – presently open only to former fighters and their families – which ensures “controlled” exodus from Pakistan.

One former fighter who took this route, explained it to the BBC before returning to India in June.

“I sold my belongings in Muzaffarabad to raise money for my family’s air travel to Nepal, from where we’ll cross into India and reach Srinagar,” he said, preferring not to give his name.

“Our passports and air tickets were arranged by a contact person in Rawalpindi city.”

He paid more than $2,000 (£1,278) to arrange travel for himself, his wife and three children. This is big money by local standards, and has kept the numbers of returnees fairly low.

Pakistani sources say just over 1,000 people, roughly half of them militants, have gone home or are in the process of doing so, since the route was opened 19 months ago.

Officials in Indian-administered Kashmir put the figure at about 500, including relatives of former militants. They expect a similar number to follow suit by the end of this year.

Pakistani authorities are now conducting a survey among the refugee population to determine how many of them want to return to their former homes. The refugees fear that they, too, may be required to travel via Nepal.

‘Stranded’

“Few people can raise the kind of money required for that route,” says a former militant commander, Bashir Ahmad Peerzada.

Mr Peerzada is married with two children, and has set up a small business in Athmuqam, a town in Pakistani-administered Kashmir. He says he is under pressure from his parents and siblings on the Indian side to come home, but he doesn’t have the money to pay for the trip.

“If India and Pakistan care for the Kashmiris, they should let them cross this arbitrary line they have drawn to divide them,” he says.

For the moment, there are no signs of this happening, and most refugees who want to return to India feel stranded – and desperate.

“It’s been 60 years, but there’s no freedom,” says Siddique Butt. “I don’t care about freedom any more. I just want to go home.”

Ashraf Jan has similar sentiments.

“Sometimes I feel like jumping into the river and swimming to the other side. But I can’t do that. I have children, a family, back at the camp.”

For these people, unless things change, a trip to Keran and a walk along the riverbank will be the nearest they ever get to a family reunion.

(BBC)