Terry Friel and Simon Denyer

SRINAGAR/MUZAFFARABAD, Feb 11 (2004) – There’s something new at night on the streets of Srinagar these days – traffic.

Indian Kashmir’s main city no longer shuts down in fear as night falls. Instead, Kashmiris now visit friends for leisurely dinners; shops and restaurants stay open and army patrols – reduced in number – no longer check everyone they pass.

With the thaw between India and Pakistan, and New Delhi’s first formal talks with moderate separatist political leaders, has come a new, relaxed atmosphere in the Kashmir Valley, the heart of the anti-Indian revolt that has killed tens of thousands.

“Earlier, my parents used to get worried if I came home a little bit late. But now… they don’t curse me,” said Umar Nazir, a 24-year-old medical student.

“The situation has changed a lot. I can meet my friends after my classes and sit in restaurants and chat until late.”

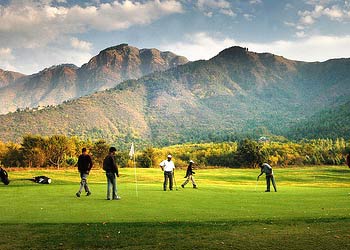

After too many false starts, many Kashmiris are warily hopeful that Islamabad and New Delhi are serious this time about ending the bloodshed in a region famously described in an old Urdu couplet as paradise on earth.

“There’s a feeling of relaxation in Kashmir,” says professor Noor Ahmed Baba, head of the political science department at Srinagar’s Kashmir University.

“There is a hope with people that ultimately the Kashmir issue will be addressed and there will be a peaceful solution.”

Things changed with the meeting of Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf in Islamabad last month.

TALKS

There, they agreed on talks – to begin next week – on a range of disputes, including Kashmir, which triggered two of the three wars between India and Pakistan and brought the nuclear rivals close to another war less than two years ago.

Delhi followed this up with its first formal talks between the main political separatist alliance, the All Parties Hurriyat Conference and Vajpayee’s hawkish deputy, Lal Krishna Advani.

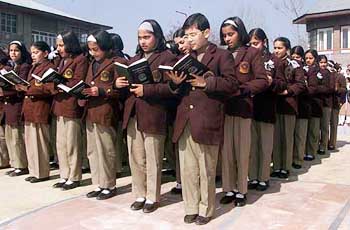

There are now fewer soldiers and more people on the streets of Srinagar, an ancient city more than 2,000 years old spread around the placid Dal Lake and its famous houseboats in the shadow of snow-capped mountains.

The main highways are still checked each morning for bombs or landmines that might have been placed by separatist Muslim guerrillas, but there are fewer army convoys ruling the roads.

“People are very optimistic. The atmosphere has changed,” says A.H. Mughal, a lecturer who works in Delhi, some 1,000 km (600 miles) by road from his home in Uri, a bustling trading post near the ceasefire line dividing Indian and Pakistani Kashmir.

“Many villages are divided in two parts. We are happy – we will meet our brothers. All families will be reunited.”

Mehbooba Mufti, a lawmaker and the face of the state government’s “healing touch” policy, is confident of change.

“Once the people make up their mind, I don’t think anybody can stop the process,” she says, sitting in her official residence in the heavily fortified compound of her father, Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Syed.

“The people are not ready to go back to the gun. They have understood it’s futile. People want peace with dignity.”

There is a new openness, too, across the frontier in Pakistani Kashmir after Musharraf called for flexibility on both sides in the search for a solution.

“One or two years ago, people used to just talk of jihad (holy war),” said Kamran, who fled from Srinagar in 1991, at the height of the rebellion against India’s rule in its only Muslim-majority state.

“But now they just talk of peace and don’t mention jihad.”

Says Taqdees Gillani, an English teacher: “Now, many things are becoming acceptable. There was a time when people who talked of independence… would be labelled traitors.

“(And) whatever the Indians said, it was taken as a conspiracy, a hidden meaning behind the words of the leadership. But this time, people want to give them a chance.”

Some feel that with hopes so high, failure now would come at a terrible cost.

“There is a bigger sense of optimism now,” says a journalist in Srinagar. “But everyone is expecting so much. If it doesn’t work out this time, it’s going to be worse than ever, bloodier.”

And despite the optimism, Kashmir is still under tight military control on both sides, and is still dangerous.

The Indian army is investigating allegations that its troops dragooned five villagers as porters and then used them as human shields in a battle with guerrillas in which the five died.

And Syed Ali Shah Geelani, who leads a hardline Hurriyat faction opposed to talks and who is seen as wielding influence over militant groups, says Indian troops continue to kill and torture innocent Kashmiris, charges the government denies.

In one recent case, he says, only one leg from a youth taken away for questioning was returned to his parents for burial.

“As far as the occupying forces are concerned, they are constantly having a barbaric attitude,” he says.

Others, too, remain sceptical, believing the hostilities have gone on too long to change now.

“We have been living with this for the past 56 years,” says Mohammed Amin Chalkoo, a 52-year-old businessman, as he supervises the unloading of a truckload of dried fruit in Lagama, on the highway linking the two Kashmirs.

“Nothing is going to happen. We have seen this too many times before.”