Firdous Syed

Though external affairs minister SM Krishna told his Pakistani counterpart Hina Rabbani Khar on the sidelines of the recent Afghan donors’ conference in Tokyo that normalisation of ties between the two countries is possible only ‘in an atmosphere free of terror,’ militancy in Jammu and Kashmir seems to have received fresh impetus.

Despite the Abu Jundal affair overshadowing the recent India-Pakistan foreign secretary-level talks, security forces have found fresh evidence of infiltration in the past two or three weeks. Talking about an ongoing operation near the Line of Control, Lieutenant General Om Prakash, the Srinagar-based 15 Corps Commander, said items recovered from six killed militants indicate that they were either a receiving party or had freshly infiltrated.

He further said there are inputs of large concentration of militants in launch pads across the LoC, which indicates the likelihood of increased attempts at infiltration in the future.’

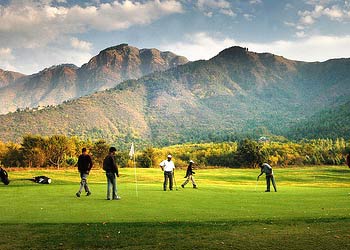

The huge inflow of tourists and the near-absence of militant attacks in recent times tempted some senior politicians to declare that the chapter of militancy is now virtually over in most parts of the state. Union health minister Gulam Nabi Azad, with misplaced belief that tourism is the panacea for all ills, proclaimed that ‘with peace and normalcy returning to the state, it was time now for the government to develop tourist spots.’

However, high-profile militant attacks within a week have put the brakes on the ‘peace has returned’ bandwagon. A sensational militant attack on the Srinagar-Jammu highway — reportedly owned up by the Lashkar-e-Taiba — has gotten the security forces worked up. The attack in Pampore in the outskirts of Srinagar, in which a soldier was killed and another grievously injured, occurred, incidentally, on the Amarnath Yatra route.

Earlier, militants had killed two police personnel within a distance of a few kilometres in South Kashmir. The annual Amarnath Yatra commenced on June 25, and in the wee hours of that day, a mysterious fire destroyed a shrine associated with a much-reverend Sufi saint in Srinagar.

The series of shocking incidents has given rise to apprehensions that something more sinister may be in the offing.

In an unpredictable atmosphere, the flurry of militant activity has, once again, broken the spell of eerie calm. The section of the security apparatus that is always quick to declare the return of peace may be tempted to categorise the recent activity as the desperate efforts of militants. But the undeniable truth is that sustainable peace never returned to the valley.

Irrespective of its internal problems and changed geopolitics, Pakistan has managed to maintain a minimum requisite level of militancy in order to keep the militant infrastructure in J&K alive. The present militant activity apparently seems to be a surge that is part of such a design. Without belittling the success of the security forces, Pakistan still holds tremendous potential to create upheaval at a time of its choosing.

Two decades have passed since the inception of militancy in J&K. From New Delhi’s standpoint, much water has flown down the Jehlum, but events seem to reoccur cyclically. In 1989, the political aspirations of the valley, misread by Delhi as mere alienation, were exploited by Islamabad to arm Kashmiri boys. Nothing has changed since then. Instead of a political solution, New Delhi overcame the challenge of militancy solely through a sledgehammer approach. A vast security apparatus established after the militant uprising helped quell militancy. Yet, what the situation would have been had the changed scenario after 9/11 not restricted Pakistan’s capability to support militancy in Kashmir is anybody’s guess.

The 2010 civilian unrest was more intense than that of 1989. According to confirmed intelligence reports, 3,000-4,000 boys were ready to cross over to pick up arms. What saved the situation was the fact that Pakistan, in dire straits, discovered that it could not exploit the situation. In the ongoing dialogue, Pakistan is disinclined to carry forward Prevez Musharraf’s four-point proposal. It believes that in the current situation it cannot force a favourable deal; Pakistan is simply waiting for a more opportune moment. New Delhi could have won Kashmiri hearts and minds with a little more accommodation; instead, it is, as usual, afflicted with perennial inertia.

(The author is a prominent columnist based in Kashmir. The ideas are his own)