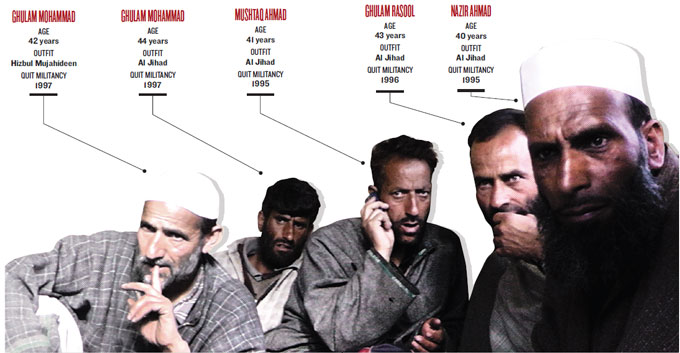

They returned to the ‘mainstream’, but normal life eludes them. Here’s a tale of former Kashmiri militants, now living in the shadow of the guns they once wielded

Riyaz Wani

SRINAGAR, Nov 16: AS night fell on 30 July 1988, two men left their homes to plant bombs with timer devices at three places in Srinagar — Akhara Building, Central Telegraph Office (CTO) and Srinagar Club. Two bombs went off, one at the CTO later that night and another at the club in the wee hours of 31 July. The message was sent across: Kashmir was ready for violence to press for Azadi.

Kashmir’s “armed rebellion” is said to have begun with these bombings carried out by the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). Yet no militant had envisaged how this would rewrite Kashmir’s history. The blasts, followed by a series of attacks on the police, started a chain reaction that prepared the stage for a full-scale revolt, and by 1989 nearly all of Kashmir was rooting for JKLF. Hundreds of youth crossed the LoC into Pakistan for arms training. The state has been a blood-soaked battleground ever since.

Looking back, some of the surviving top-ranked militants of that time exude a mix of nostalgia and ambivalence. “We took recourse to violence in desperation. When all means of peaceful resistance were closed off, violence became the only way to make our voice heard,” says former JKLF chairman Javed Mir. Besides Yasin Malik, Mir is the only survivor from JKLF’s four-member HAJI group, which also included Ishfaq Majid Wani and Abdul Hamid Sheikh.

Sheikh was among the first to cross the LoC in March 1988. Malik, Wani and Mir followed him in June. On their return, they formed two separate groups and prepared for an armed struggle.

‘Reduced to naught’

Twenty-four years later, life has come full circle. Though a few like Mir are still the face of the separatist movement, most of the others have returned to the “mainstream”. Yet, they find the going tough.

Take Abdul Qadeer Rather. In 1988, Rather hosted two persons from PoK who had come to help JKLF prepare for the first attack. He later sold his tractor to buy an Ambassador car to ferry youth to Kupwara in north Kashmir, from where they crossed the border. Rather quit militancy in 1993.

Now, ailing at his home in Lasjan on the outskirts of Srinagar, Rather says the separatist politicians have let Kashmir down. “I don’t regret having helped start the militancy, but I think it has come to naught because of Hurriyat’s policies,” he says.

Rather’s namesake, Abdul Qadeer Dar from the pro-Pakistan Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), has a similar story. Dar was in Afghanistan for arms training during the heyday of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Hizbe-Islami chief, and Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Tajik leader of the Northern Alliance. In 1990, Dar returned to Kashmir and worked as HM’s “divisional commander” in north Kashmir. Apprehended in 1993, Dar quit militancy after three years in jail.

A small-time businessman now, Dar, 45, often tries to look back and make sense of his life as a militant. He is part of the J&K People’s Rights Movement — a 7,000-member body that addresses problems faced by former militants.

“Kashmir has moved on from the violent 1990s, but we are still mopping the fallout,” says Dar. “We have learnt that no one else would address our problems.” In 2007, he organised a meeting at a Srinagar hotel where several former militants narrated their personal histories.

‘Haunting’

IT hasn’t easy for Dar and his ilk to adjust to a quotidian life and its pressures. Most of them were reduced to doing odd jobs to make ends meet. Their militant background made them ineligible for government employment, or even a passport. According to a list prepared by J&K Police’s Intelligence Wing, around 60,000 families in Kashmir are on the “security blacklist”.

The result has been two-fold: while most former militants have become “outsiders” in their own society and cynical about life, there are some who bask in the hangover of their militant past. “The political atmosphere and public sentiment made us pick up the gun. Driven by emotions, we were not mature enough to understand the politics of it all,” says Ashraf, a former combatant, who had crossed the LOC in June 1990. Of the 11 others who had crossed over with him, seven died in combat with security forces. “It’s just my good fortune that I’m alive,” he says.

Ashraf runs a shop in Baramulla town, and is also writing his own memoir. “It will be a chronicle of our sacrifices and sufferings — a reminder to society that we exist and are being passed over now,” he says.

Unlike many who “fell by the wayside,” Ashraf has made a successful transition to normal life, with his only son Abid pursuing a doctorate in Political Science. “I started from nowhere, became a part of the armed campaign for Azadi and ended up nowhere again,” he sums up his life.

Javed Ahmad Wani, too, shares a complex relationship with his militant past. Wani rues his wasted youth, but is also nostalgic about “when his life had a purpose”. Most former militants accept that recourse to the gun was pointless, but it’s not a comfortable admission. Many of them privately credit themselves for ushering in a dramatic departure in Kashmir’s history, which contributed to its international recognition as a conflict zone.

Wani writes poetry in Kashmiri under the pseudonym ‘Zouq’. It is his way of recapturing the “mood and sentiment” of his militant past. “This city, I am told, has been plundered of spring. The outsider comes and does as pleases him. The outsider throws out the landlord…” goes one such poem.

‘Let down’

Though most former militants are in dire need of institutional support to help them lead normal lives, the state government has no proper rehabilitation programme for them. So far, the practice has been to refuse financial support to the families of killed militants. Help is offered only when the police certify that a person was killed by militants.

“The J&K government should take a cue from Punjab and the Northeast, where rehabilitation policies for ex-militants have been successfully implemented,” says Abdur Rasheed, a former militant. A demand also raised by the J&K Welfare Association. In early October, Rasheed and his colleagues observed a symbolic hunger strike at Srinagar’s Press Enclave.

Sharing their unenviable lot are the militants who recently returned from POK under the government’s rehabilitation plan. Around 117 Kashmiris returned with their families, only to find that the government has no follow-up plan for them. “We have to start our lives all over again. We have no jobs, our children are struggling to get education, but the government has no plan for us,” says Shabir Ahmad Dar of Shopian, who returned to his village early this year with his wife and two children.

With a relatively peaceful Kashmir looking uncertainly at the future — and some residual militancy still smouldering — former militants occupy a contested space in Kashmiri society.

“We are expected to stay true to the cause, and any perception of deviation turns us into State agents in people’s eyes. Security agencies, too, view us with suspicion. We are frequently summoned to police stations and security camps, and any dissent we express is seen as rebellion,” says Rather. “We live in this society, but feel as if we are not a part of it.”

(Courtesy: Tehelka)