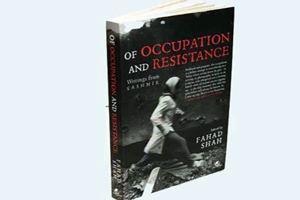

A new anthology on Kashmir paints a grim picture

Mayank Austen Soofi

Women beating their chests. CRPF beating the boys. Death by guns. Death by hangings. A new book on Kashmir tells the stories of a strife-torn region from the perspective of novelists, journalists, activists, photographers, anthropologists, teachers, students and a gravedigger.

Of Occupation and Resistance: Writings from Kashmir is edited by Fahad Shah, who manages the online journal The Kashmir Walla. The anthology surveys the valley’s private and public distresses since 1988. This was the year when militant violence first appeared in the picturesque land.

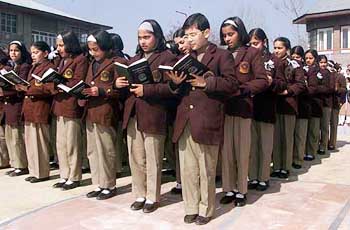

Charting the evolution of new ways of protests among Srinagar’s youth, Shah says in his introduction Blood Will Be Avenged, “The curbs on freedom of speech in Kashmir and the indifference to local requests and demands have led to the emergence of rap singers, underground graffiti artists, painters, writers, photographers and filmmakers. There are websites and blogs that express the realities within Kashmir, or narrate brutal tales from the conflict.”

In The Life of a Rebel Artist, MC Kash, who describes himself as a “resistance rapper”, talks of how hip-hop made him “wanna rebel and speak up!” He writes: “I remember listening to Eminem’s tracks and really just trying to figure out his words at first.

He was funny, abusive, angry and hated. I don’t know why, but I could relate to it all—the fury, the rejection, the protest. Deep inside, I felt as if I had found a new beginning. I knew that hip hop was what I would listen to for years to come.”

Kash was first noticed in 2010 with his track I Protest. He followed it up with two albums, Rebel Rebulbik and Liberation: A Tribute to Shaheed Maqbool Butt.

Co-founder of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front, Butt was hanged and buried in Delhi’s Tihar jail in 1984.

In The Meaning of Maqbool Butt, P.G. Rasool, a columnist in Kashmir, writes: “It is interesting to note that Maqbool Butt’s whole family has sacrificed for the cause. One of his brothers disappeared outside the state in mysterious circumstances while he was in search of legal aid for Maqbool. His second brother, a key figure in the 1988-89 armed struggle, was killed in a road accident in Srinagar. A third brother got killed in his native village in an encounter with the army… Butt has not been forgotten by the people. It seems to them that he is still in jail challenging the mighty Indian state, posing a titanic moral dilemma for authorities. To date, he is a symbol for his oppressed people.”

I found the symbol of Kashmir’s misery in the death certificate of a 17-year-old boy who, according to Shah in his piece Report Amidst Sobs: Omar Died After Arrest, was tortured by the police and the CRPF after being pulled out of a Friday afternoon slogan-shouting in August 2010. His death certificate showed the cause was “respiratory hypertension with severely deranged blood gases, diffuse intrapulmonary haemorrhage and blunt trauma on the chest”.

Touching upon the matter of displaced Kashmiri Pandits, Delhi-based novelist Siddhartha Gigoo says in Looking Back at the Roots: “Who am I? Where have I come from? What will become of me? The old Pandit generation is fading away. The young are losing the memory of their own ancestry and lineage. Have they been able to memorialise aspects of this shrinking identity and a litany of losses through the arts and literature? No. haunted by a sense of extinction, I shiver when I come across people who seek to assess and weigh losses and assign degrees to suffering without even knowing what they lost.”

The book’s saddest portion is in the end—Notes on the Contributors, a section that unwittingly lays bare the tragedy of Kashmir. Anthropologist Ather Zia “works on militarisation, human rights and gender in Kashmir”.

Atta Mohammad “is a gravedigger from North Kashmir who has buried more than 235 unknown bodies in unmarked graves (of which some were mass graves) in a burial ground close to his house”. Hashim “is a stone thrower in Kashmir. (Further details withheld.)”