Tariq Bhat

A few kilometres ahead of Kashmir’s Sopore town, on the banks of the Jhelum river, lies Seer Jagir—the village where Afzal Guru was born and brought up. The last stretch to the village passes through an Army camp. A sentry gestures all vehicles to slow down as part of protocol.

The mud road winds into the river bank where two women in Kashmiri woollen gowns—pheran—are chatting at the steps of a pier. The Jhelum flows at a lazy, winterly pace. The bare branches of the Chinars seem to reach out to the rows of the houses that make up most of the village.

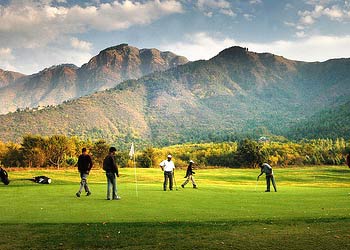

Seer Jagir hides no signs of affluence that the hundreds of world-famous apple orchards have brought to most of Sopore and its surrounding areas. Sopore, after all, is called chhota London. As the tempting aroma of fresh bread wafts from a rundown bakery nearby, villagers greet us with a cautious Asalamu alaikum.

Ask for Afzal’s house, and they point to the two-storeyed brick house with a lawn. It is locked. Hilal, Afzal’s younger brother, fled after Ajmal Kasab was hanged. “He was terrified and told his wife that Afzal could be next,” says a villager. “They left in a hurry.”

Elder brother Aijaz had moved out with his family a few years ago. Afzal’s wife, Tabassum, had moved to her parents’ house at Azad Gunj in Baramulla soon after he was arrested in 2001. “She visits occasionally,” says Muhammad Yousuf, a villager. Last September, Afzal’s mother, Ayesha Begum, died of a stomach ailment. His father, Habibullah Guru, had died of cirrhosis about 35 years ago.

Afzal’s neighbours, friends and relatives cannot believe that he had a role in the Parliament attack. He was to be a doctor. Someone who would make Seer Jagir proud. When Afzal got into medical college, the whole village celebrated.

Having seen tough times after losing his father at the age of 10, Afzal was about to chart a new course for himself and the village. Those were times when Kashmir was peaceful.

It was restive peace, perhaps. Kashmir’s chequered history soon took another dangerous turn. Young men started taking up guns. Crossing into Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir and becoming mujahideen became an obsession for many in the early ’90s. Even their families did not matter to them.

Sopore and its adjoining areas, including Seer Jagir, became a strong base for militants. Foreign militants, especially from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Sudan, had a free run. The area turned into a ‘liberated’ zone, with militants proudly displaying the weapons seized in encounters with Indian security forces.

The dread of some fierce militants like Akbar Bhai and Ibn-e-Masood, a Sudanese chemical engineer who had studied in London, loomed large. Both were killed, but their bravado rubbed off on many young minds in Sopore. Separatist aspirations ran high. Afzal, too, fell for the charm of the gun.

Guns

In his 2006 mercy petition to the President, Afzal explained that “during those heady days”, like “many thousands of youth” in the valley, he was inspired by Omar Mukhtar’s banned film Lion of the Desert, which depicts the story of a teacher who fights for liberation of his people and is eventually executed.

Afzal joined the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front. That, however, explains his ideology was not indoctrinated by the dominant Jamaat-e-Islami, majority of whose adherents formed the Hizbul Mujahideen. Afzal was different from most other recruits. He apparently had social and educational moorings.

Afzal was a village boy who had toiled to enter medical college. His maternal cousin, Dr Abdul Ahad Guru, a renowned gastroenterologist, was his inspiration. Guru helped Afzal join Jhelum Valley Medical College in 1988. Incidentally, militants gunned down Guru in 1994.

On shunning militancy and returning from PoK, Afzal could not resume his MBBS course. He moved to Delhi and graduated (via correspondence) in political science from Delhi University.

Afzal then wanted to join Delhi School of Economics. He gave tuitions to raise money, and stayed with his cousin, Shaukat Guru, who had married Afshan Navjot, a Sikh girl who had converted to Islam. A few days after the attack on Parliament on December 1, 2001, the police arrested Afzal, Shaukat, Afshan and S.A.R. Geelani, a Kashmiri lecturer in Delhi University.

The police accused them of collaborating with Jaish-e-Muhammad militants who attacked Parliament.

The five militants who mounted the audacious attack ever on the edifice of Indian democracy were killed in the shootout. The country lost seven security force personnel, including a female CRPF constable.

The charges levelled against Afzal were posession of explosives at his place in Delhi; conspiring to commit and knowingly facilitate the commission of a terrorist act; and harbouring and concealing the deceased terrorists knowing that they were terrorists. He was charged under the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (POTA).

A special anti-terrorist court sentenced Afzal, Shaukat and Geelani to death, and Afshan to five years’ imprisonment. They moved the Delhi High Court, which acquitted Afshan and Geelani.

The Supreme Court upheld the acquittals and reduced Shaukat’s sentence to 10 years’ imprisonment, but it enhanced Afzal’s sentence. He was given a triple life sentence and a double death sentence. However, on August 4, 2005, the Supreme Court noted in its judgment that there was no evidence that Afzal belonged to any terrorist group.

“But as is the case with most conspiracies, there is and could be no direct evidence of the agreement amounting to criminal conspiracy. However, the circumstances, cumulatively weighed, unerringly point to the collaboration of the accused, Afzal, with the slain fidayeen terrorists,” said the judgment.

“The incident, which resulted in heavy casualties, had shaken the entire nation, and the collective conscience of society will only be satisfied if capital punishment is [awarded] to the offender.”

Some legal experts like N.D. Pancholi, who is one of Afzal’s lawyers, believe he did not receive a fair trial. “The amicus curie did not plead his case sufficiently,” Pancholi said. “He did not cross-examine the witnesses. Afzal wanted to change him, but that was not accepted.”

Pancholi hopes the delay in deciding on Afzal’s plea could lead to “pardon and reprieve for him”. He explains: “There is nothing like a mercy petition under the Indian Constitution. But Article 72 provides for right of pardon and reprieve to convicts. The delay regarding Afzal’s fate could actually amount to pardon and reprieve, as in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case.” Apparently, this provision was one of the reasons for expediting Kasab’s hanging.

Ghazals

Now with Afzal’s life hanging in the balance, THE WEEK traced several people who were closely associated with Afzal since his childhood to piece together the story of a man who aspired to become a doctor and enter civil services, but ended up on the death row. Afzal’s neighbours and childhood friends still have vivid memories of him and his family. “His father was a flamboyant character,” says Muhammad Sultan, a neighbour. “In the 70s, when most villagers struggled to make ends meet, he owned an Ambassador car.”

Abdul Ahad, another neighbour, adds, “When most people had no access to television, he bought one for his kids. The whole village would assemble at their home on Sundays to watch movies.”

Habibullah had been into transport and timber business. He died young. The responsibility of providing for the family fell on the young shoulders of Aijaz, only a few years older than Afzal. He took a job in the veterinary department and also doubled as a small-time timber merchant. “Aijaz ensured Afzal’s schooling did not suffer,” says cousin Farooq Guru.

The family suffered another blow when Riyaz, the youngest of the four brothers, died. Riyaz, too, had been in Delhi, where he sold Kashmiri artwork. A shattered Ayesha’s health deteriorated. It was Afzal who helped her, from fetching water from the river to running errands. “He would cook, wash clothes and clean the house,” says a woman in the neighbourhood. “Come summer or winter, Afzal always helped his mother.”

But Afzal did not ignore studies. He and other village kids would board a naav from their village to reach Doabgah Government High School.

“Sometimes, we walked through the fields and orchards, and then crossed the Puhuru rivulet to reach school,” recalls Molvi Bashir Ahmed of Doabgah, Afzal’s schoolmate. “He was very good at sports, theatre and cultural activities.”

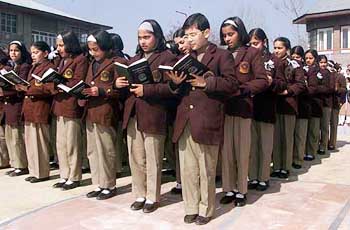

Mubashir Marazi, who was Afzal’s senior in school, says the ‘terrorist’ often was the parade commander in school on Independence Day. “The teachers loved him for his humour and brilliance in extracurricular activities,” he says.

Back then, Kashmiri Pandits were the backbone of education and administration in Kashmir. Afzal grew under the influence of respected teachers like Prannath Soori, Rattan Lal, Trilokinath Raina and Sham Sunder Gartoo.

“They inculcated the best values in students,” says Ahmed. “They never discriminated among students, and Afzal was one of their favourites.” The only thing one of the teachers disapproved in him was his passion for swimming. “Once we were enjoying a bath in the river and one of the teachers took away our clothes,” Ahmed recalls with a smile.

But it was Afzal’s misguided passion for ‘liberation’ in his later life that proved too costly. “Dropping out of medical college always haunted him,” says a relative. “In his childhood, his father lovingly called him doctor. He wanted Afzal to become a doctor and Afzal knew that.”

A doctor who studied with Afzal in JVMC recalls him as jovial and loving. “He was quite a hit with the girls for his love for music,” he says. “He often sang ghazals, and the girls enjoyed that.”

Back then, JVMC had no hostels. Some students stayed at a private hostel in Bemina. “Afzal and I were there,” says another doctor, requesting anonymity. “He loved poetry. Poets like Mirza Ghalib and Alama Iqbal were his favourites. There was a big portrait of Iqbal in his room.”

Another batchmate describes Afzal as a guy who studied hard and scored average marks. “He cleared all the regular examinations in the first year,” he says. “The college closed down for some months due to strife and then we appeared for our first professional exams. Afzal missed them. After that, we never saw him.”

Years later, after graduating in Delhi, Afzal married Tabassum, who was related to his mother. He was initially employed by his relatives, but later started a business in surgical goods in Srinagar. He often travelled to Delhi on business. In 1999, Tabassum gave birth to a son. Afzal named him Ghalib.

“Then, one fine day, he was arrested from Parimpora in Srinagar,” says Ghulam Muhammad, his father-in-law. “News reports said he was involved in the Parliament attack. The Supreme Court has not said there is evidence against him. Yet, he has to be hanged to satisfy the ‘collective conscience’ of the Indian nation!”

Aijaz says his family has left the issue to Allah. “Afzal has repeatedly asked us and Tabassum not to beg mercy. Allah will deliver him from darkness to light,” he says. In fact, in his mercy petition, Afzal wrote: “I cannot ask for forgiveness for something I have not done.”

Tabassum has always refused to speak to the press. Still, we meet her at Sopore’s Guru Nursing Home, where she works. “I have left it to Allah now,” she says. “He [Afzal] is not afraid of anything. Allah will protect him.”

The hospital staff respect her. They call her Pyari didi. She spends most of her time at the nursing home. However, Ghalib is the focus of her attention. He is in Class VIII and is ‘protected’ by the family, round-the-clock.

When Afzal’s family met President A.P.J Abdul Kalam in 2006 to seek clemency, Ghalib apparently told him that he wanted to become a doctor but was not hopeful, as his father was jailed. “Afzal wants his son to do a Ph.D,” says Ghulam.

“The last time he saw Ghalib, Afzal told him go for higher studies and always stand by his mother.”

Let Ghalib’s journey not go like his father’s.

Hanging in the balance

* December 13, 2001: Five terrorists attack the Parliament complex, killing 9 people.

* December 15, 2001: Delhi Police take Afzal Guru, member of the terrorist outfit Jaish-e-Muhammad, into custody from Jammu and Kashmir.

* June 4, 2002: Charges are framed against Afzal Guru, S.A.R. Geelani, Shaukat Hussain Guru and Afsan Guru.

* December 18, 2002: Death sentence awarded to Afzal, Geelani and Shaukat. Afsan is let off.

* August 4, 2005: Supreme Court upholds Afzal’s death sentence, which is to be carried out on October 20. It commutes Shaukat’s death sentence to 10 years’ rigorous imprisonment and acquits Geelani.

* October 3, 2006: Afzal’s wife, Tabassum, files mercy petition with President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, which he forwards to home ministry.

* August 10, 2011: Home ministry sends a letter to President Pratibha Patil recommending death penalty. She defers her decision.

* November 16, 2012: President Pranab Mukherjee sends back Afzal’s petition to the home ministry seeking a re-look at its opinion.

* December 10, 2012: Home Minister Sushilkumar Shinde says he will examine Afzal’s file after Parliament’s winter session concludes on December 22.

* December 13, 2012: BJP gives notice for suspension of Question Hour in Lok Sabha to discuss the delay in Afzal’s hanging.

* January 11, 2013: Home minister says he is yet to take a decision on the mercy plea.

(The author is correspondent, the Week)