Tariq Ahmad Bhat

SRINAGAR, Sept 12: “In Muzaffarbad life was easy, but here (Kashmir) we are starving, and this is supposed to be the paradise on Earth,” says Fauzia Hassan, the mother of three kids and a resident of Muzaffarabad in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK), who has returned home after 20 years.

These men, during their youth, crossed the Line of Control (LoC) for firearms training to pursue an elusive goal of Aazdi (freedom).

But then, they preferred to stay back, and raised families after marrying local women in PoK and Pakistan. But, they always longed for the day they would return home.

When the Centre and J&K government announced clemency for those Kashmiris who have crossed the LoC from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 2009, more than 300 people returned to Kashmir via Nepal—an expensive, circuitous but relatively safe route than the designated points through Wagah or Attari in Punjab or IGI airport in New Delhi. Though the men are happy to return to their roots, their spouses are not.

“In Muzaffarabad we had our own house, a good business and some land,” elaborates Fauiza, “Here we are starving. No one has come forward to help.”

Fauiza came to Kashmir a few months ago, with her husband Ghulam Hassan, a resident of Kupwara, and three children.

At their home at Pazipora village, he was shocked to see that his brothers had razed their ancestral home and built two separate houses for themselves. Though, they hosted him initially, hospitality soon gave way to bitterness.

“We could have involved the village elders to retrieve our share in the property, but he (Ghulam) says he returned to his homeland not for the property,” Fauzia said.

“Let them have it.”

Ghulam makes both end meet by selling vegetables on cart. Fauzia’s biggest worry is the education of her children.

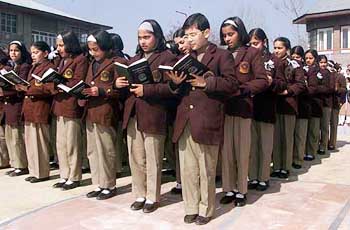

The schools have refused admission to her daughter stating that she has come from Pakistan, and hence, needs to clear lots of formalities. However, her two sons have got admission in a local school after villagers intervened.

Same is the case with Shaheena Akhtar wife of Tariq Khan. Khan, a resident of Chattabal in Srinagar, who crossed LoC 21 years ago to become a militant, has retuned home.

He, however, stayed back waiting for the situation to improve. In Muzaffarabad, he worked in the municipality, and also worked as a rickshaw driver.

The couple has two children—a girl and a boy. In Kashmir, his brothers greeted him well initially, but soon, he was left to fend for himself.

“We have rented a room for 1,000 rupees,” said Shaheena. “Even managing that is difficult. I sold my gold ring to pay for my daughter’s admission fee.”

Most of the women in the PoK say the locals view them strangely and do not care about their problems.

“Here we are treated like strangers,” said Ghulsan Bibi, who married Bashir Ahmed Lone, a resident of kalaroos, Kupwara.

Lone crossed the LoC in 1995 with a group of Al Barq militants, but did not join militancy. For sometime, he stayed in local madrassas, and learnt to drive a rickshaw. He then married Gulshan.

“He (Lone) is jobless and my sons have not got the admission yet,” Gulshan said. “If we were in Muzaffarbad we would not have been starving like this.”

Most of these women now meet at a rented house of Javid Ahmed Dar. His wife Saira is now planning to start a sewing centre for these women.

Hailing from an affluent family in Karachi, Dar’s distant relatives in Rawalpindi sought her hand for him.

After marriage, Saira moved to Pindi. He worked as a driver for a transport company, and she managed a small school. Her father gifted her a plot of land in Karachi, which they sold for just one thousand Pakistani rupees hours before leaving for Nepal.

“Life was easy in Pindi. We sold all our belongings, including our plot, as we were returning home. But here, it is very tough,” says the mother of three children.

She stitches cloth for money. “Here, they pay just 50 rupees for a shalwar-kameez. That is nothing compared to Pindi.” Dar has finally been employed as a driver on a salary of 3,000 rupees.

“One thousand is the rent for this room, and there is school fees and four mouths to be fed,” says Siara. “We are living a life of penury. My parents in Karchi would be shocked to hear all this.”

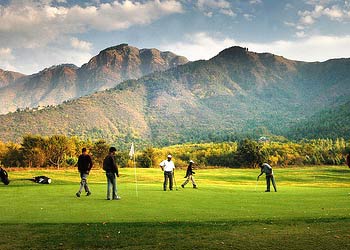

Shabeena, who is married to Muhammad Ashraf of Chattabal, 51, says she has heard a lot about Kashmir. “Except the beauty, Kashmir has nothing. Muzaffarbad is very small compared to Kashmir, but people are generous.”

Qulsum Ashraf, 17, and her brother Riyaz Ahmed, 10, had also fled Kashmir. The siblings came to Kashmir after their father, Muhammad Ashraf Mir Gilkar, decided to return home. In 1993, Ashraf married Shabnum in Muzaffarabad, when she was in her secondary school. Two years on Qulsum was born.

“On Eid, I used to have lots of fun, but on my first Eid in Kashmir, I stayed in this room mourning about my future.” Shabana, her mother, an arts graduate, said their decision to come to Kashmir made them beggars.

“We are no one here. We have no identity or a future,” she said. “If they can’t do anything about our future, they should hand us over to the Red Cross.”

(Author is correspondent The Week)